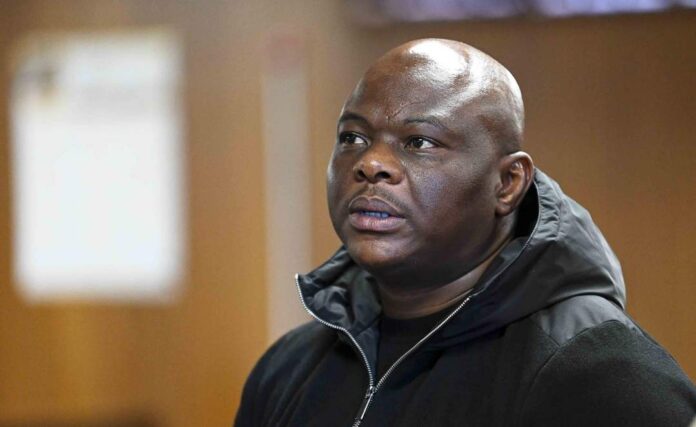

In the high-stakes, shadow-drenched world of South African government procurement, few names once carried as much weight—or as much controversy—as Edwin Sodi. For over a decade, Sodi was the undisputed poster boy for what critics dubbed the "tender-driven empire." He was a man whose proximity to the highest echelons of political power seemed to render him untouchable, a "King of Tenders" who lived a life of unapologetic opulence while the public infrastructure he was contracted to build often crumbled into ruin.

However, the walls have finally closed in. The empire built on state-funded largesse is now being dismantled, piece by piece, by the very legal systems it once appeared to circumvent. The definitive blow came not from a single criminal conviction, but from the cold, hard reality of commercial insolvency. His flagship company, NJR Projects—strategically rebranded as the G5 Group in an apparent attempt to distance itself from mounting failures—has been liquidated. The catalyst? A staggering R50 million debt that has effectively stripped Sodi of his corporate shield.

But the real story isn't just the liquidation itself; it is the "web of deceit" Sodi allegedly spun to keep his empire running long after it had become a hollow shell. As an investigative look into this "crumbling empire" reveals, Sodi’s business model was less about engineering and more about a "Ponzi-style" cycle of debt and redirection. While creditors were left empty-handed and essential services like clean water were denied to thousands, Sodi continued to bid for new contracts, using fresh state funds to maintain the illusion of success. This is a cautionary tale of greed, political protection, and the inevitable "day of reckoning" for those who treat the national treasury like a personal ATM.

The R50 Million Hammer Blow

The definitive end of Sodi’s perceived invincibility arrived two weeks ago in the Johannesburg High Court. Judge Nelisa Phiwokazi Mali delivered a ruling that effectively pierced the corporate veil—a legal mechanism typically protecting directors from personal liability. Mali ordered Sodi, in his individual capacity, to pay Hollard Insurance a staggering R39.8 million. With interest factored in, that figure rises to a crushing R50 million.

This debt stems from a failed project to upgrade the 65-bed Parys prison into a 240-bed facility. In March 2019, the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) awarded NJR Projects a R282 million contract. The bank provided an advance payment of R23 million, guaranteed by Hollard Insurance. However, by February 2023, the DBSA terminated the contract, citing "poor performance," and demanded Hollard honour the performance guarantee.

When NJR Projects stopped repaying the advance payment in October 2022, the bank issued a default notice. Hollard, forced to pay the bank, then turned its sights on Sodi. Because Sodi had personally signed deeds of indemnity and suretyship, he was left holding the bill for a company already in the throes of liquidation. This judgment marks a significant shift in South African law, where the "corporate veil" is increasingly being lifted to hold "tenderpreneurs" accountable for the wreckage they leave behind.

A "Zombie" in the Water Industry

The liquidation of NJR Projects (G5 Group) was actually set in motion earlier, in April last year, by a creditor named Case Hire North West. The plant-hire company had leased heavy-duty construction vehicles to Sodi’s firm but was never paid. In their liquidation application, Case Hire’s legal team was blunt:

"Based on the controversial history and media reports of the respondent in relation to failed payment obligations and/or failed governmental and/or municipal contracts pertaining to construction and/or upgrading projects involving the respondent and its controlling individual, former director and shareholder Mr Pheane Edwin Sodi, it will also be just and equitable to wind up the respondent and allow for insolvency inquiries to take place in respect of the finances and/or possible liabilities of the respondent’s directors, both past and present."

This "zombie" status—operating while technically dead—is a hallmark of Sodi's later years. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Rooiwal Waste Water Treatment Plant debacle. Awarded a R291 million contract to repair the plant in Hammanskraal, Sodi’s consortium failed to deliver. The site remains a monument to mismanagement, and the consequences were literal: a deadly cholera outbreak in the area that claimed lives.

The City of Tshwane has since launched a frantic effort to blacklist Sodi. Last Thursday, the municipality finally submitted a formal application to the National Treasury to have Blackhead Consulting, the G5 Group, and Sodi himself barred from bidding for government contracts for up to 10 years. For years, officials claimed they "couldn't find" Sodi at his known addresses to serve him with the necessary letters—a delay that allowed him to continue operating in the shadows.

The Asbestos Scandal and the Political Shield

To understand how Sodi operated for so long, one must look at the "political protection" that reportedly shielded him. Sodi has never been shy about his connections, counting Deputy President Paul Mashatile among his close friends. His testimony at the State Capture Commission was a rare window into the world of "tenderpreneurship," where millions in "donations" flowed from his accounts to the ruling ANC and its high-ranking officials.

The most infamous example is the R255 million Free State asbestos audit. Sodi’s company, Blackhead Consulting, was part of a joint venture that secured the contract to identify asbestos roofs in the province. The Special Investigating Unit (SIU) later found that the project was a sham—hardly any work was done, yet millions were paid out. Sodi currently stands as one of 17 accused in the ongoing trial, alongside former Free State Premier Ace Magashule.

The SIU’s findings were damning, revealing a "web of deceit" where procurement regulations were systematically violated. Yet, even while facing criminal charges for fraud, corruption, and money laundering, Sodi was still able to secure new work. It was a classic "Ponzi-style" model: use the proceeds from Tender B to pay off the most aggressive creditors from Tender A, all while skimming enough off the top to fund a life of extreme luxury.

The Social Media Fallout and the Missing Millions

For years, Sodi’s social media presence was a curated gallery of wealth. He flaunted a fleet of high-end Ferraris, Bentleys, and a R48 million palatial mansion in Fresnaye on the Atlantic Seaboard. Between 2015 and 2023, he reportedly spent at least R148 million on high-end properties, including 31 apartments in Cape Town’s Harbour Arch.

But as the liquidators circle, the "social media" fallout has turned toxic. The man who once showcased the vibrant colours of his luxury car collection is now being pursued by lawyers across provincial borders. The "missing" millions are the primary target of the liquidation inquiries. Where did the money go? How much was diverted to political "donations," and how much is hidden in the intricate centres of his property portfolio?

Liquidators are now tasked with tracing every cent. The R50 million debt to Hollard is just the tip of the iceberg. As one former employee noted in recent investigations, the operations were organised in a way that prioritised the appearance of success over the reality of service delivery. The investigation into the "missing" millions will likely reveal a complex network of offshore accounts and shell companies designed to frustrate creditors.

A Legacy of Failure and Accountability

From the R282 million Parys prison project to the R291 million Rooiwal plant, the trail of incomplete work is vast. The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) even appointed him as one of six companies to maintain critical pump stations with a budget of R368 million, despite his horrific track record. This lack of oversight allowed a "zombie" company to maintain control over "the most important bulk water supply system in the country."

The City of Tshwane’s recent application to the National Treasury is a critical step. If successful, it will mean that Sodi and his companies will be unable to bid for government contracts for up to a decade. This blacklisting is not just a punishment; it is a necessary measure to protect the public purse from a man who has demonstrated a consistent disregard for his contractual obligations.

The Inevitable Day of Reckoning

The fall of Edwin Sodi is more than just the story of a failed businessman; it is a documentary-style look at the "crumbling empire" of state capture. It simplifies the complex world of liquidation for the public, explaining why Sodi can no longer hide behind corporate veils to protect his assets.

The City of Tshwane’s move to blacklist him is a sign that the tide is turning. The "political protection" that once seemed absolute is evaporating as the public demands accountability for the "deadly water" and the "missing" millions. For the residents of Hammanskraal, who have lived with the consequences of Sodi’s failures, this day of reckoning is long overdue.

This is a cautionary tale of greed. It demonstrates that while the wheels of justice may turn slowly, they eventually reach even the most powerful. For the man who treated the national treasury like a personal ATM, the account has finally been closed. The King of State Tenders has been dethroned, not by a rival, but by the weight of his own "web of deceit."

Key Details of the Sodi Empire Collapse

|

Project/Entity

|

Value

|

Status

|

|

NJR Projects (G5 Group)

|

N/A

|

Liquidated in April 2025

|

|

Hollard Insurance Debt

|

R50 million

|

Personal liability judgment

|

|

Rooiwal Waste Water Plant

|

R291 million

|

Incomplete; linked to cholera outbreak

|

|

Free State Asbestos Audit

|

R255 million

|

Subject of ongoing criminal trial

|

|

Parys Prison Upgrade

|

R282 million

|

Terminated for poor performance

|

|

Cape Town Property Portfolio

|

R148 million

|

Purchased between 2015 and 2023

|

Follow Us on Twitter